It seems past is catching up on Great Britain and this very past claims for reparations. Since the beginning of May, there are ongoing negotiations between British government’s solicitors and former Kenyan insurgents - the Mau Mau- victims of crimes and tortures from colonial authorities in the 1950s.

Then a British colony, Kenya saw the rise of the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. It was basically an insurrectional and anticolonial movement protesting against the oppression applied on the Kikuyu population - the ethnic group most of the rebels belonged to.

The Mau Mau revolt turned into a guerrilla and they started to attack the interests of both Europeans and Kenyans who were on the side of the colonial system.

It’s in this context that the bloodiest repression of the history of the British Empire took place, targeting both the Mau Mau fighters and the Kikuyus who were suspected to be part of the rebels. Between 80.000 and 300.000 people were locked up in work camps. The revolt was defeated in 1956 and Kenya eventually became independent in 1963, while integrating the Commonwealth – the organization which gathers around the British crown most of its former colonies.

In October 2012, the High Court of Justice gave to three Mau Mau veterans the right to prosecute the British government to seek redress. In reference to the will of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to appeal against this decision, the UN rapporteur on torture, Juan Méndez, issued a public warning to the British state: “In our opinion, the answer the British government gave to the most vulnerable and aged victims of tortures committed -and admitted- by the British is shameful”.

Then a British colony, Kenya saw the rise of the Mau Mau rebellion in 1952. It was basically an insurrectional and anticolonial movement protesting against the oppression applied on the Kikuyu population - the ethnic group most of the rebels belonged to.

The Mau Mau revolt turned into a guerrilla and they started to attack the interests of both Europeans and Kenyans who were on the side of the colonial system.

It’s in this context that the bloodiest repression of the history of the British Empire took place, targeting both the Mau Mau fighters and the Kikuyus who were suspected to be part of the rebels. Between 80.000 and 300.000 people were locked up in work camps. The revolt was defeated in 1956 and Kenya eventually became independent in 1963, while integrating the Commonwealth – the organization which gathers around the British crown most of its former colonies.

In October 2012, the High Court of Justice gave to three Mau Mau veterans the right to prosecute the British government to seek redress. In reference to the will of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to appeal against this decision, the UN rapporteur on torture, Juan Méndez, issued a public warning to the British state: “In our opinion, the answer the British government gave to the most vulnerable and aged victims of tortures committed -and admitted- by the British is shameful”.

The British colonial archives scandal

The opening of the colonial archives on the 18th of April 2012 was the triggering factor that started to accelerate everything. Accusations of tortures and abuses the Foreign and Commonwealth Office always denied, eventually encountered an historical and official echo. Several matters are clearly highlighted in those archives. Firstly, abuses –including violations, tortures, castrations, murders, collective punishments, etc- were, indeed, committed in Kenyan camps. Secondly, these abuses were admitted and covered in high places.

In this regard, one of the most polemical pieces commented in the High Court of Justice was a note written by Eric Griffith-Jones -the colony’s administrator- in which he wrote mistreatments imposed to convicts were “distressingly evocative of the living conditions in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia”, although he concludes “if we have to sin we need to do it quietly.” The state knew and kept secret those documents for approximately sixty years –when it didn’t merely destroy them. This is the third lesson one can learn from the study of the colonial archives: close to 80% of them had already been destroyed by the authorities – while another significant part remains secret - according to an estimation.

In this regard, one of the most polemical pieces commented in the High Court of Justice was a note written by Eric Griffith-Jones -the colony’s administrator- in which he wrote mistreatments imposed to convicts were “distressingly evocative of the living conditions in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia”, although he concludes “if we have to sin we need to do it quietly.” The state knew and kept secret those documents for approximately sixty years –when it didn’t merely destroy them. This is the third lesson one can learn from the study of the colonial archives: close to 80% of them had already been destroyed by the authorities – while another significant part remains secret - according to an estimation.

Deny or ignorance?

That’s why the publication of those documents left the British state with no other choice but to admit the crimes it committed.

Until now, the governmental defence consisted in invoking prescription on one hand and, on the other hand, redirecting the claim to the Kenyan state, legally responsible since the independence in 1963.

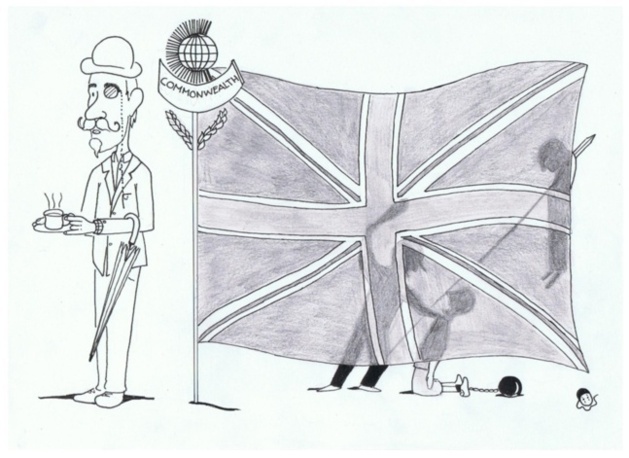

This system of defence is very evocative of the British mentality concerning its former colonies. The myth of the British Empire as a civilizing benefactor was widely disseminated and still exists through the Commonwealth.

In the collective imagination –and also for some historians- the British colonization remains a model of tolerance contrary to the French one, regarding to what happened in Algeria.

Indeed, despite the scope of political and historical implications, the colonial archives opening in April 2012 was only covered by The Economist and The Guardian, in an article entitled « Deny the British empire's crimes? No, we ignore them ». The Guardian’s columnist -George Monbiot- denounced the British society blindness and reminded the work of Caroline Elkins -Harvard professor and Pulitzer Prize winner in 2006- for her book Britain's Gulag: the brutal end of the Empire in Kenya. After ten years of investigation, she describes in this book horrors that were inflected to the convicts and challenges official figures affirming that almost all of the Kikuyu population –that is approximately one million and a half people- was detained in work camps. Such works aren’t denied, simply ignored.

Until now, the governmental defence consisted in invoking prescription on one hand and, on the other hand, redirecting the claim to the Kenyan state, legally responsible since the independence in 1963.

This system of defence is very evocative of the British mentality concerning its former colonies. The myth of the British Empire as a civilizing benefactor was widely disseminated and still exists through the Commonwealth.

In the collective imagination –and also for some historians- the British colonization remains a model of tolerance contrary to the French one, regarding to what happened in Algeria.

Indeed, despite the scope of political and historical implications, the colonial archives opening in April 2012 was only covered by The Economist and The Guardian, in an article entitled « Deny the British empire's crimes? No, we ignore them ». The Guardian’s columnist -George Monbiot- denounced the British society blindness and reminded the work of Caroline Elkins -Harvard professor and Pulitzer Prize winner in 2006- for her book Britain's Gulag: the brutal end of the Empire in Kenya. After ten years of investigation, she describes in this book horrors that were inflected to the convicts and challenges official figures affirming that almost all of the Kikuyu population –that is approximately one million and a half people- was detained in work camps. Such works aren’t denied, simply ignored.

Snowball effect

Though the Department of Foreign Affairs declared it wants a debate to be organised on the colonial past, negotiations which started at the beginning of May with the Mau Mau veterans soon revealed the will to smother the facts as quickly as possible. 10.000 people in Kenya might be concerned by potential compensations.

But the state fears that the Mau Mau reparation would spur a snowball effect and encourage other voices to rise in order to claim for compensation, especially the one of EOKA’s former rebels –an organisation which fought against the British occupation in Cyprus since 1955. No doubts new complaints from all four corners of the British Empire would damage, even more, the Commonwealth reputation.

But the state fears that the Mau Mau reparation would spur a snowball effect and encourage other voices to rise in order to claim for compensation, especially the one of EOKA’s former rebels –an organisation which fought against the British occupation in Cyprus since 1955. No doubts new complaints from all four corners of the British Empire would damage, even more, the Commonwealth reputation.