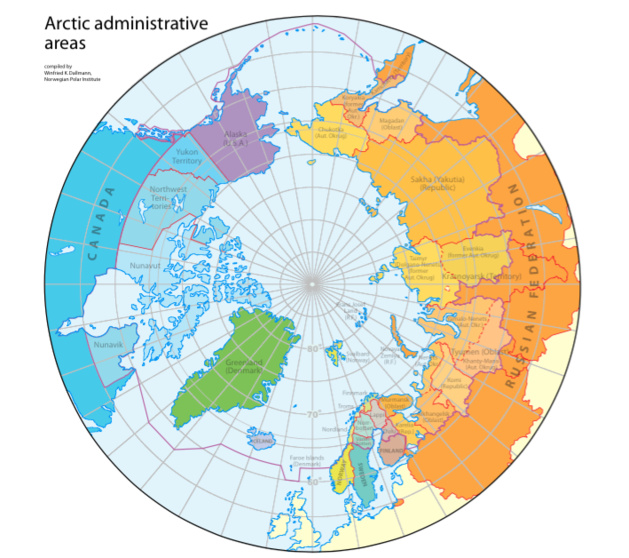

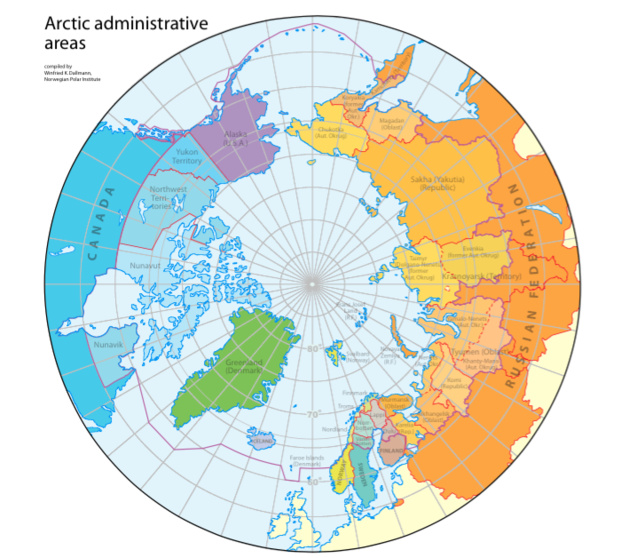

The area is hard to define geographically because its structure is essentially determined by the climate there. 8 sovereign states have territory in the Arctic; these are Iceland, Finland, Sweden, Russia, the United States, Canada, Norway and Denmark. Only the last 5 of these have a seaboard, and therefore an exclusive maritime area. Issues over energy sources and the environment distract attention from a political situation which is actually relatively calm; however, the melting ice caps and the lack of a clearly defined legal structure in the region have thrown this stability into imbalance.

THE SQUARING OF THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

The Arctic is a key area in terms of international governance as well as the fight against global warming. The arctic environment is largely spared from human pollution, yet it is fragile and highly symbolic. When discussing climate change, the first thoughts that spring to mind are often the melting ice caps, and the endangered polar bears. The area is at the forefront of climate change both because of its abundance of endangered species and because the area is suffering the consequences of global warming faster than the rest of the world. Even though the southern hemisphere suffers more from climate change than the northern hemisphere, estimates suggests that temperatures in the Arctic area are increasing between two to four times as fast as the average in the rest of the globe!

The issue is that the Arctic is a rich area in many natural resources, such ashydrocarbons, minerals, metals, and rare earths, as well as an abundance of fishing resources. In a report from The United States Geological Survey in 2008, which is still relevant today, experts estimated that the area holds 29% of global natural gas reserves and 10% of oil reserves. This is a strategic area for both scientific exploration - a lot of countries, even distant ones, such as India, own arctic research bases - and energy and mining exploitation, Ironically, the melting ice allows a better access to these resources and therefore an increase of these exploitations.

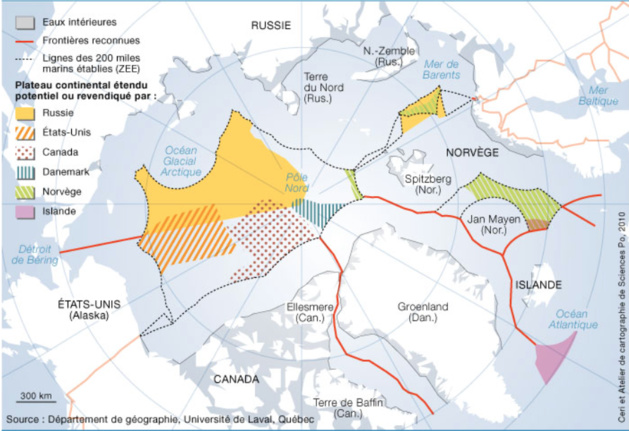

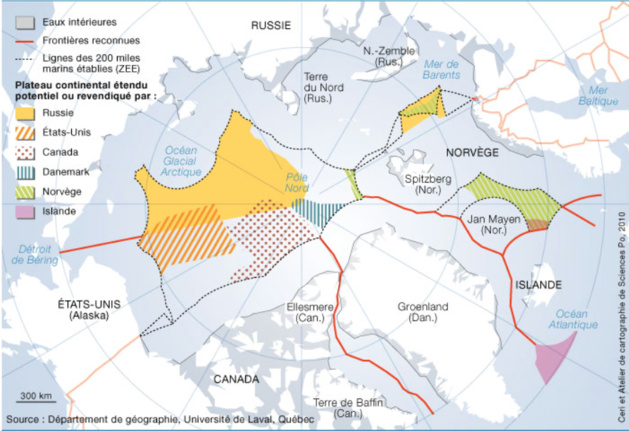

It was in this context in the early 200s that, the UN, via the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, granted to coastal States the opportunity to take legal recourse to extend their area of maritime sovereignty – settled by the Convention of Montego bay of 1986. Russia and Canada primarily but also Denmark (who are involved in the Arctic because of their sovereignty in Greenland) and Norway have submitted their claims to this commission, considering their own continental shelf. Some of these claims have been wildly unrealistic, as in the case of Russia, which claimed to have complete sovereignty of the North Pole.

Therefore, States such as Norway or Canada seem to be behaving in an almost schizophrenic way. There can be no doubt that these nations are genuinely concerned about climate change and the risk of oil spills;however their economies are mostly based on hydrocarbons exploitation and export. Maintaining their sovereignty and access to these resources is crucial for them, although this is completely contradictory with their environmental goals.

APPEASED GOVERNANCE AREA…

In reality, despite some acts such as the planting of a Russian flag in the North Pole in 2007, these territorial claims are mainly settled amicably between the nations, just as in the case of Norway-Russia about Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago. Several disagreements remain, such as the sovereignty of the Hans Island – which Canada and Denmark both claim – or the status of waters located on the Northern part of Canada. On this last point, the dispute remains since the 70s with the United States, who make a particular claim that their military ships should have total freedom of movement- like on every oceans - whereas Canada considers that this area falls under its own internal waters.

No binding legal framework allows regulating the relationships in this area. Despite everything, the Arctic Council, acting as a forum, allows all the relevant stakeholders to gather around the same table, as well as a number of observer States such as France, Italy, Germany, as well as China, India or Singapore. Other organizations such as the Nordic Council or the Barents Euro-Arctic Council offer discussion frameworks formal to local powers and opportunities to cooperate. Overall, it seems that despite heavy liabilities between Russia and the rest of the Arctic area countries – which are all associated with NATO – the area is more favourable to cooperation than confrontation. The sanctions taken against Russia after the Crimea’s occupation did not have any impact on the situation in the arctic, and Moscow continues to cooperate willingly with its counterparts from the West, including militarily, counting Norway in 2010 and 2011.

… HOWEVER, THIS IS A FRAGILE BALANCE

However, two factors can disrupt this balance of powers. The first concerns intervention and representation rights in the region, a factor which is largely redundant. Regarding the countries of the Arctic G5 – i.e the five coastal States – the respect of the sovereignty in the area is crucial, and the demonstration of interest by some foreign powers like China has been seen as a threat. For this organisation, it is tempting to claim ownership of the Arctic territory.

The joint declaration of Illulissat in 2008 – excluding the 3 other Arctic area States as well as the observer members of the Arctic Council – wished to prove this. They committed to solve their mutual disputes in a peaceful and concerted way, thus avoiding a universalization of the area that a UN regime, for instance, would have represented. This was the same case regarding a motion for common management of fishing. These meetings between the 5 countries, which may be seen as a form of privatization of the Arctic in the eyes of the other Arctic area nations, seem unlikely to be repeated in the future. This is partly due to the increasing power of the Arctic Council, but is also due to the lack of unity within the G5.

The other long term risk for stability in the region concerns the possible opening of maritime routes in the North-West (through Canada) and North-East (through Russia). On the one hand, this already implies a possible solution to the disputes concerning the status of waters situated at the North of Canada. But above all, the potential opening of these roads could lead to the redefinition of the sovereignty spaces in the area, including the status of the straits.

While some nations such as Iceland see an opportunity to strengthen their position in the international business, others such as Canada are afraid of the impact on the local environment.. The challenge is even higher considering that the seaboard is steep, and that the infrastructure hardly lends itself to constructing harbours.

While some nations such as Iceland see an opportunity to strengthen their position in the international business, others such as Canada are afraid of the impact on the local environment.. The challenge is even higher considering that the seaboard is steep, and that the infrastructure hardly lends itself to constructing harbours.

Despite the ice melt opening these seaways for a short period of the year, we have to keep in mind that they are far from being fully exploitable. Even during the summer period, when the ice field sufficiently decreases, the floating growlers can sink ships – leading to additional insurances. Therefore, not only is there a need to build more resistant (and more expensive) ships, there must also be a reduction in speed of trade to improve manoeuvrability. Finally, all of these factors highlight that the global trade relies on punctuality, and these roads will not offer enough guarantees for the business for several decades. Hopefully, by then, the fight against climate disruption will have taken a different turn.