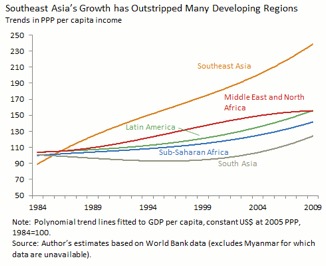

The export-orientated strategy combined with an outward look aimed at attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) has left Brazil at the mercy of external factors upon which much of its economic growth depends. The result: a series of boom and bust cycles which do little to serve the wide range of domestic issues faced by the South American giant. Following the debt-growing tactic of import-substitution, many hailed the export-led policy when the Asian Tigers experienced incredible growth rates from the 70s to the early 90s along with ensuing development.

The right conditions

From then onwards, LEDCs have been encouraged to follow in the Tigers’ footsteps, which means more neo-liberalism, and zero state interference. Indeed, development policies over the last 60 years have been dominated by the mainstream approach, embedded in liberalism and, more recently, neo-liberalism, focusing on growth only. This is a misguided conception of the characteristics of the East Asian model.

More than once the international community has dismissed the “Asian Miracle” as the result of a set of Asian cultural and institutional values that could not be replicated elsewhere . But essentially, their model for economic development is state-led. That is not to say that high investment is not important or does not account for the high levels of growth but redirecting that investment towards key industries is the model’s core. The Tigers made good use of FDI, investing in key sectors whilst protecting others from the volatile nature of foreign investment. Domestic political conditions are crucial to the success and legitimacy of state-led growth . The political economist, Francis Fukayama, points out that the entire experience in LEDCs is flawed from the outset by very different initial institutional starting points: you either have the right conditions or you don’t.

The right conditions

Investment in education has been praised as one of the most important aspects of the Asian model. In contrast with Hong-Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea’s highly educated work force, Brazil ranks as 54th in mathematics out of 57 countries and 48 out of 61 countries in reading abilities according to an OECD survey . Primary education was ranked 119th in the world . A large company in educational field, Pearson, ranked South Korea as number two in terms of education systems, while Hong-Kong, Japan and Singapore ranked third, fourth and fifth respectively , a trend which the OECD’s latest PISA survey confirms.

Although currently high-ranked in terms of competitiveness, Brazil’s future international competitiveness will depend on a political decision to spend public resources to transform its lower class and lower-middle class , in other words, putting to good use the remainder of its labour force that is currently being wasted. More than one million lives in the favelas (shantytowns) of Rio de Janeiro alone. The absence of the state is felt keenly in the Brazilian favelas lining the outskirts of the big cities where gangs have taken over.

This leads us to the subject of the role of the state in development. As previously discussed the East Asian governments reached deep down into society. In turn this created well-structured interest groups, reliability on efficient civil services but it also minimised political opposition . An ambiguous approach to democracy is another right condition in which development bloomed in the Asian Tigers. Although authoritarian, these governments were strong and stable.

Brazil, in contrast, struggles with a weak form of democracy, with educational deficits, violence and insecurity still plaguing many of its cities, and the intractability of the favelas remind us of the weakness of the Brazilian government whose democratic legitimacy lies within the illusion of its promises to the millions living on the margins of society. Although it is the world’s seventh largest economy (World Bank, 2012), the 2013 protests, the largest demonstration movement since 1992, against increases in price transportation and later high levels of government corruption and the huge spending on the upcoming World Cup and Olympics, underline the huge socio-political issues the Latin American country has.

States of contrast

Brazil is the largest state in terms of area and population in the Latin America and the Caribbean region, and being the world’s fifth largest country, it highly contrasts with the small and less populated states of East Asia. It has an ethnically diverse population especially when compared to the relatively homogenous and highly cohesive societies of the Asian Tiger countries, and has high income and integration disparities between different race groups. As a result of these contrasts, attempts to apply the East Asian development package model can fail to produce growth or generated chronic corruption and economic disaster. Although growth has not been so much of an issue for a country as rich in natural resources as Brazil, its high levels of government corruption and the Brazilian debt crisis are testimonies to these underlying problems that cannot be ignored.

That is not to say that Brazil has not made remarkable progress. Brazil has weathered the economic crisis better than others and ever since the new millennium 13 million have escaped poverty and 12 million, extreme poverty. But Brazil cannot depend on following the Tigers’ economic development model - high investment as a source of growth is unreliable and the country does not have the political conditions required to be able to use the model for fruitful development.

The country may be on its way to becoming a global player but it remains the 3rd most unequal Latin American country and 10th most unequal in the world with 4,600 people dying in 2008 in criminal, drug, militia and police-related violence in Rio alone. So whilst Brazil rises on the international scene straddling along a wealthy elite, it leaves behind a non-negligible part of the population living on the edge, excluded from the fruits of this growth and that will remain marginalised until the government reaches out.