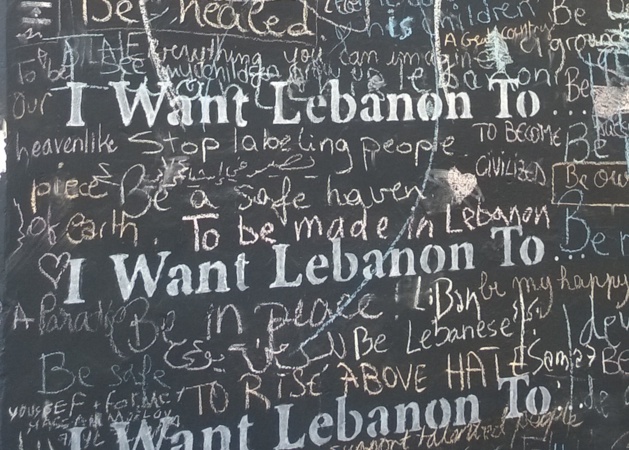

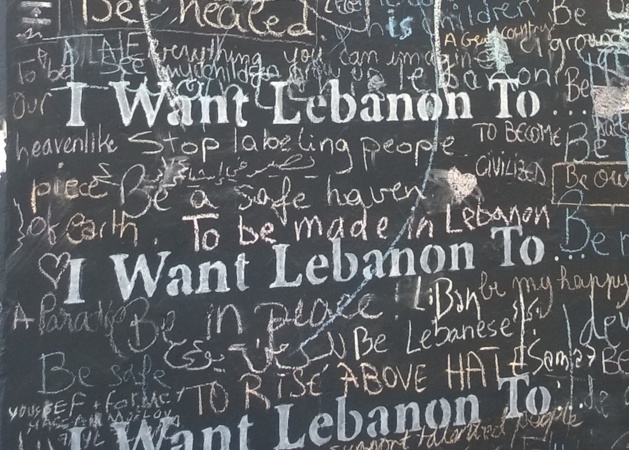

Under the Fouad Chehab Bridge, Beirut. Credit Salomé Ietter

The geopolitical situation of the neighbourhood means a lot in any given country. This is especially true for Lebanon. Long before the war, which was civil in name only, the status quo of the region changed, above all in 1967, with the Israeli victory. In Lebanon, divisions appeared between pro-Palestinian groups - ready to fight against Israel - and nationalist groups – more preoccupied with the sovereignty of their country. As in other Arab countries, both the defeat and the demonstration of power by Israel in 1967 crystallised the underlying tensions, which dated back to the creation of the state of Israel. Some groups, mostly left and Muslim, turned the cause of the Palestinian refugees into their leitmotiv. Thus, Palestinian, pro-Palestinian, and nationalist militias developed simultaneously.

On April 13th 1975, members of the Lebanese Phalanges killed 27 Palestinian passengers of a bus. The Lebanese Phalanges Party, also known as Kataeb, is mostly a Christian party. It denies accusations of extreme nationalism. In spite of the alliance that bound the different Christian parties during the war, under the auspices of the “Lebanese Forces”, dissensions appeared in the later years of the conflict: the Phalanges were considered too sectarian, even fascist. The nationalist aspect is likely dominating the religious aspect; however, in times of war, every indicator of identity is used to mobilize the population. As Amin Maalouf describes it, identities change according to the circumstances. This tendency to associate religious identification with political identity led to what could be defined as a civil, religious and interfaith conflict. This dark April 13th was designated as the official date of the start of the conflict. From the massacre and the arming of the Palestinian groups, trouble escalated.

The “battle of the hotels” emptied the big hotels of Beirut almost immediately. This battle destroyed one of the most powerful symbols of the economic boom: Lebanese hospitality and tourists reception. The hotel Holiday Inn, which opened three years before its destruction, provided 500 rooms and a panoramic restaurant. It stood for the trust that prestigious hotel companies placed in the country. Today, the Holiday Inn is still an empty shell, offering the tourists the sad spectacle of its walls strewn with bullet impacts.

Cultural life - also a symbol of Lebanese modernity - quickly suffered from the fights, as shown by the remains of the first and greatest Lebanese movie theatre, or the wonderful – but empty - structure of the Grand Theatre, which has undergone rebuilding efforts for years, after hosting famous European and Middle-Eastern groups and artists in the past.

Who waged war?

As shown in these pictures, the heart of Beirut has become a battlefield, between forces that are hard to identify, even today: there are Lebanese, of course, but also some foreign fighters or opportunists. Alliances evolved during the war, as well as the implication of foreign powers. Many Lebanese feel like this war was “waged by others, and for other nations”. Dania shares this point of view: “I still do not really understand who waged this war. They are fanatic groups, armed, from the inside and the outside. People who defended the Palestinian cause for their own purposes, and others who rejected it. You do not need many people to spread terror. One person who beheads another, and that’s it: you are into war”.

The beginning of a descent into war only hangs by a thread, a life. This idea can also be found in the murderous escalation of the conflicts that punctuated these so-called years of “civil war”. As Dania underlines it, if the person who perpetrates the triggering act claims to be driven by an ideological opinion - in addition to his/her project of political opposition or support - both causes are quickly associated. Thus, many rumours concerning a Christian-Israeli cooperation circulated.

After the murder of Bachir Gemayel, the son of the founder of the Lebanese Phalanges, the Lebanese Forces responded with massacres of men, women and children, in the infamous camps of Sabra and Shatila, under Israeli supervision. Israel invaded South Lebanon from 1978, and its operation “Peace in Galilee” allowed it to besiege Beirut in the summer of 1982. This also caused the creation of Hezbollah, whose trademark was defined as the fight against Israel. It was the turn of Syria to enter the conflict in 1976, initially to protect the Christians, and then to defend the Palestinians. The game of alliances and opportunism was based on fragility and affinities of faith, thus amplifying the desires of revenge.

The Green Line and the separation of faiths: civil war or cooperation?

For the Lebanese, in 1975, a new life began. A life made of controls, checkpoints, segregation, curfew, and anxiety. Back then, Dania’s family lived – and still lives – in the district of Hamra, mostly inhabited by Muslims, but where Christian families still live in the same building as Dania’s family. Yet, from 1976, the Christians of West-Beirut were strongly urged to move in East-Beirut, on the other side of the infamous “Green Line”. Its name comes from the vegetation that grew along Damascus Street, abandoned by the population.

The “Yellow House”, or Barakat building (from the name of its ancient owners), constitutes another symbol of the time before the war, for the citizens of Beirut. Because of its architecture, the diversity of its inhabitants, but also its unfortunate strategic position – on the demarcation line. The beautiful house of the 1920s has become another empty shell, a façade whose bullet impacts tell about a very sinister heritage. Following a project of partnership work with France, the house will become, in several months or years, the city museum of Beirut.

The National Museum, along Damascus Street, was significantly affected by war and snipers shot, which damaged some masterpieces. There again, the memory of war is still fresh. A twenty-minute long video pays tribute to the men and women who strived before, during and after the war, to save thousand-year-old works and archaeological treasures.

Yet, when you look at the testimonies, segregation – although promoted as the safest solution by politicians – was not so obvious, as a matter of fact. Admittedly, for her whole youth, until 1988, Dania could see neither the city centre, nor East-Beirut. However, some Christians who lived in her building in West-Beirut did not follow orders to join the Christians of East-Beirut: they had placed their loyalty in their friends and neighbours.

For 15 years, daily life had been made of war times and quiet times. In this second instance, life almost went back to normal. Schools sought to make up for the lost time, some shops re-opened. Dania’s school, located in Hamra, stayed opened for the entire war. Now, she deeply thanks the head teacher of the French and Protestant school, who stayed, despite the conflicts, to provide education to children.

In fact, Dania mostly recalls positive moments and even laughs about some memories: “hiding in the theatre during the dictation exam, that was cute. When we were children, we did not suspect that any exam could mean our incoming death”. When the peaceful times ended, bombings sometimes hit the district of her school. “Sometimes, we stayed at school for hours. We were hidden under the covered playground of the gymnasium. During the district wars, the most dangerous thing was to move”. As she points out, “There was a bit of an organisation to step outside. The militias had to rest, eat, so we knew when we could get out”. Therefore, daily life had to be planned so as to take as few risks as possible.

Everyone lived on their own, and missiles answered one another. An explosive hit one of her schoolmates. But despite all these horrors, Dania did not confront them, neither directly nor physically. Thus, relatively speaking, she says: “We were very lucky”. She remembers precisely the night when her building was bombed. While they gathered in their shelter, Dania’s father came to the rescue of his neighbour, stuck in his flat, which had been set on fire by a bomb. “My father is very strong, he was a hero during the war and helped save people. He was even given a revolver, so as to be the safety delegate of our building”.

She remembers a neighbour who yelled: “They will cut our heads”, to which the other neighbour replied: “Shut up, will you? There are kids!”. Today, she laughs about those panic reactions, those screams, but she remembers them very well. This night of bombing is the only one that evokes the memory of war so vividly within her. “Above all, I was afraid of the sound. It never entered my mind that I could be killed or beheaded. But I was scared of the noise, scared for my parents and my sister”. At dawn, they all went out into their district. “We found the cars under the fragments of buildings. Every glass was shattered … except ours! Daddy said: 'We are lucky, we will not have to pay for the glasses'”. She remembers her neighbour’s uncontrollable fits of laughter - they deemed themselves lucky in their misfortune. “I asked why people were laughing so much, and they answered they laughed because we were still alive.”

There used to be a very strong connection between Christians and Muslims in the building. In this place, one’s identity was not solely based on religion. Because they were better informed about some threats, her father’s Christian friends advised him about the detours he had to follow and the best ways to take. Thus, Dania’s parents survived. Some other episodes, a bit funnier, marked this period of her life. So, some daily life events were magnified by the living conditions. Dania loves to speak about the Christmas night, when she was six years old, which was celebrated between Christians and Muslims. This year, Santa Claus was the hairdresser, who was very thin. Dania found it odd: a skinny Santa! “Inside the socks, we found chewing gums and chocolates. And I said: 'This Santa is a scrooge!' Years later, I understood that many shops were closed, and we did not have enough money”.