What do you know about Mongolia? A Mongol Empire with warriors on horses amid giant arid steppes? It is a large and relatively unknown nation… but this could all change. An ex-USSR nation, sandwiched between two powerful neighbors China and Russia, Mongolia begins two gigantic mine operations in 2013 that will undoubtedly disrupt the economy and regional, or even worldwide, geopolitics. With a foreseen substantial growth rate, Mongolia is about to change considerably. And so, what are the consequences for its population?

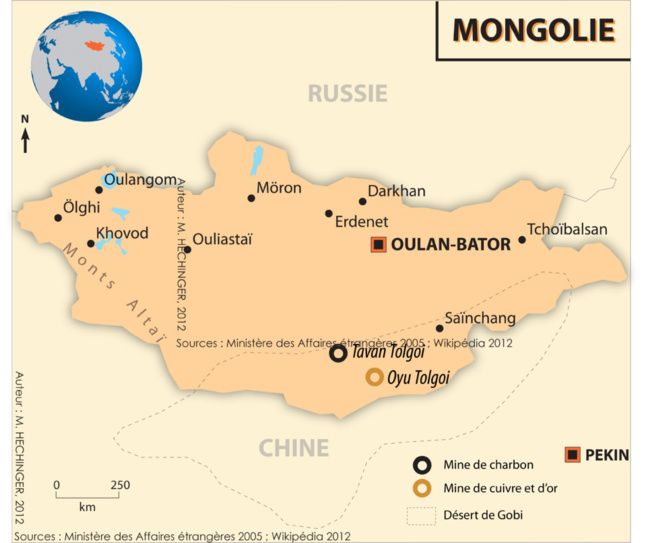

Mongolia prepares itself for this « mining boom » in 2013. In a few months, it will introduce two mines, Oyu Tolgoi and Tavan Tolgoi, in the middle of the Gobi desert, transforming the economic landscape of the region. These mines are estimated to be able to supply Chinese manufacturing industries with carbon for two centuries. The Gobi desert, unexploited until now, turns out to be a treasure-trove of coveted resources with gold, carbon, copper, and uranium. It now holds the world’s biggest copper mine, and could contain high-quality carbon deposits. Among the Chinese, Russian, and Australian investors who have grasped the market, Australian mining giant Rio Tinto which holds the biggest shares, while Areva holds its prospects for uranium.

2013 : rebirth of Mongolia

These deposits, unknown ten years ago, have earned Mongolia the title of « South-East Emirates », which will no doubt launch their economy. In 2010, Mongolia’s economic growth rate was 6.4% while in 2013, it is expected to be over 20% - the highest growth rate in the world.

The country is changing quickly. The transformation is most evident in its capital, Ulan Bator, country where almost half of the Mongolian population resides. A business district was born to welcome the new generation of wealthy Mongolians and foreign investor headquarters. Thanks to its goldmine of resources, Mongolia dons the cloak of a new world power.

But this power is nothing like its famous ancestor, the Mongolian Empire, where Genghis Khan dominated the entire Asian continent. Although this new Mongolia appears powerful, it is essentially a puppeteer of its prevailing clients, China and Russia. The exploitation of Mongolia’s mining resources provides vast but unequal economic growth, wherein foreign investors benefit from the export of raw materials at the expense of local populations.

With this economic boom will come tough tides; Mongolia’s new position in the international resource industry puts the nation before an oncoming avalanche of political challenges it has never faced before.

The country is changing quickly. The transformation is most evident in its capital, Ulan Bator, country where almost half of the Mongolian population resides. A business district was born to welcome the new generation of wealthy Mongolians and foreign investor headquarters. Thanks to its goldmine of resources, Mongolia dons the cloak of a new world power.

But this power is nothing like its famous ancestor, the Mongolian Empire, where Genghis Khan dominated the entire Asian continent. Although this new Mongolia appears powerful, it is essentially a puppeteer of its prevailing clients, China and Russia. The exploitation of Mongolia’s mining resources provides vast but unequal economic growth, wherein foreign investors benefit from the export of raw materials at the expense of local populations.

With this economic boom will come tough tides; Mongolia’s new position in the international resource industry puts the nation before an oncoming avalanche of political challenges it has never faced before.

Mining exploitation: political, social, environmental stakes

The mining boom affects all aspects of Mongolia as a nation, politics being the first. The question of resource exploitation took the spotlight during the election campaign last summer when competing parties (MPP, ex-communist party in power during the USSR era, and the Liberal Democrats) debated whether the State should nationalize these mines. The current coalition government does not yet have an answer to this question. The real question is whether the State stands a chance against foreign enterprises admist scandals of electoral fraud and corruption. The underlying issue is ultimately the redistribution of the wealth generated by the exploitation.

The social consequences of these mines are vast and numerous. New cities with population of 100,000 are cropping up all over the region, housing migrant mining workers. This massive influx into previously deserted arid regions is problematic as the Gobi desert is not equipped with sufficient administrative infrastructures, or educational and public health institutions.

The impending construction needs are urgent: a third of Mongolia’s three million inhabitants live below the poverty line. Inequalities will inevitably increase in the coming year. As illustrated already in Ulan Bator, yurt shantytowns stand at the foot of towering skyscrapers.

Finally, the mine poses two major environmental problems in the region: of water and dust. The few farmers who live in the Gobi desert see their wells going dry, their stock animals dying and their farms disappearing. Like the coming miners, the farming population already suffers serious health problems from the dust from the trucks and construction sites. And this is all before the mining exploration even begins.

The social consequences of these mines are vast and numerous. New cities with population of 100,000 are cropping up all over the region, housing migrant mining workers. This massive influx into previously deserted arid regions is problematic as the Gobi desert is not equipped with sufficient administrative infrastructures, or educational and public health institutions.

The impending construction needs are urgent: a third of Mongolia’s three million inhabitants live below the poverty line. Inequalities will inevitably increase in the coming year. As illustrated already in Ulan Bator, yurt shantytowns stand at the foot of towering skyscrapers.

Finally, the mine poses two major environmental problems in the region: of water and dust. The few farmers who live in the Gobi desert see their wells going dry, their stock animals dying and their farms disappearing. Like the coming miners, the farming population already suffers serious health problems from the dust from the trucks and construction sites. And this is all before the mining exploration even begins.